Why do we create labyrinths?

On confusion, defense, trusting paths and remembering journeys

(Editorial note: in this piece I use the term labyrinths and mazes interchangeably. My limited study shows that this is common practice among labyrinths/mazes scholars.)

Lately, I've been drawn to labyrinths as a problem-creation tool.

Multiple societies use labyrinths in their history, rituals or culture as a form of passage and I'm thinking about who creates them. The process of creating a maze to solve a problem sounds like adding more confusion, more convolution to otherwise straightforward goals and destinations. But perhaps, in the creation of mazes and their convolutions, we are forced to contemplate the non-linear, the non-obvious. Because of this property, mazes are also used as spiritual devices, as tools to contextualize and hold the concept of the subconscious, as a metaphor for life.

There are two broad categories of mazes.

There's a Unicursal maze, which usually means that there is one complete path from point-of-entry to center or point-of-entry to point of exit. You cannot get lost navigationally in a unicursal maze because there's only one way to go. You can however, lose your mind, as the paths usually tend to be very circuitous and winding, even when you sense/see/perceive that you are close to your goal. Best case, if you persevere enough, you are guaranteed to reach the exit. Worst case, you can always retrace your steps to return to the beginning of the maze. The only real choice you make with a unicursal maze is whether to enter it all.

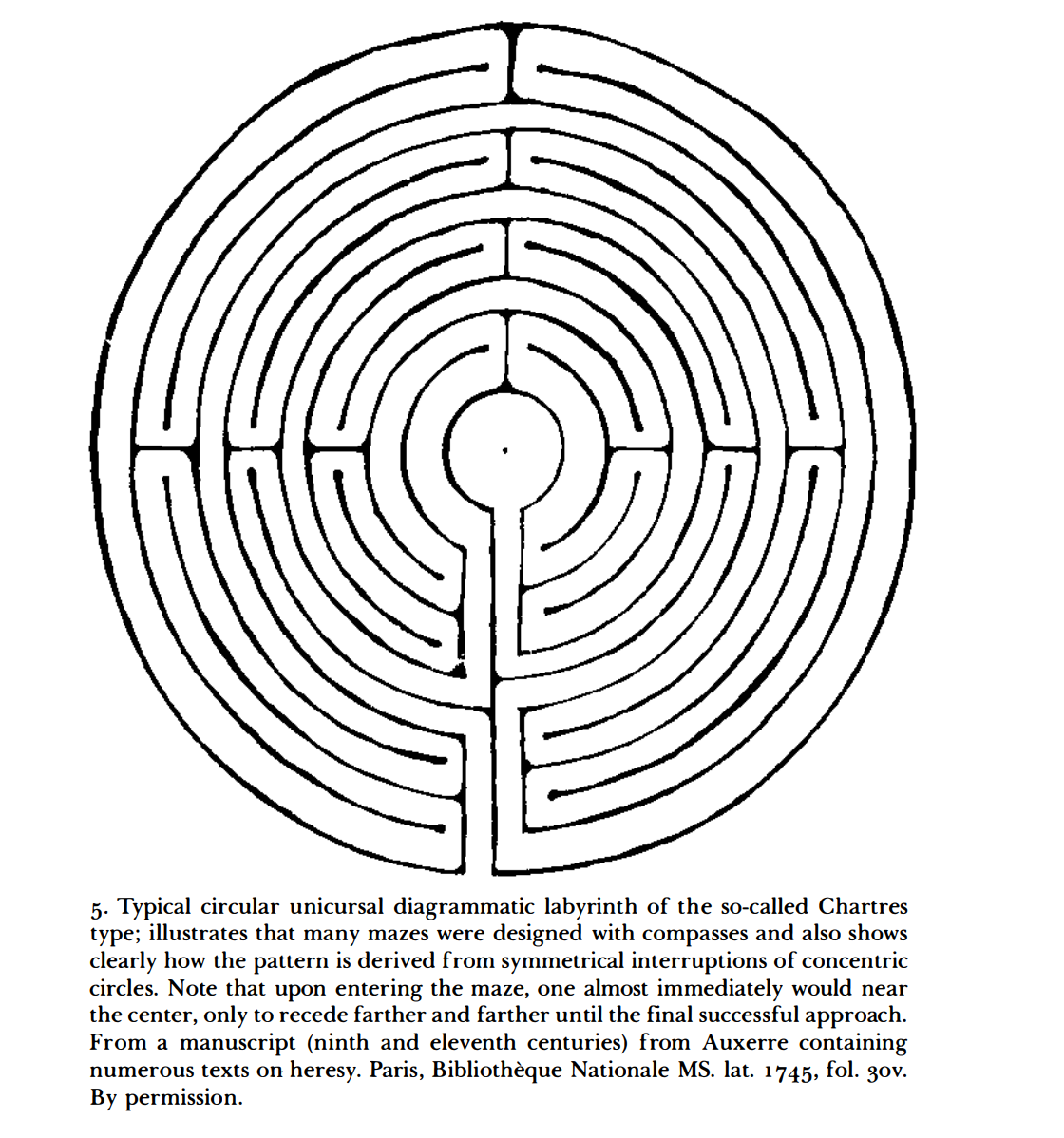

Unicursal maze design based on the labyrinth in the Chartres Cathedral in Paris. The unicursal model is meant to mimic the path of a pilgrim’s journey to the Holy Land. Image from Citation 1.

Unicursal mazes are usually made through partitions of concentric circles or spirals. As Penelope Reed Doob describes in The Idea of the Labyrinth from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages, traversing a unicursal maze usually makes you curse the maze-maker, and is often used as a metaphor for the journey of life itself . There's only one way to go. You didn't necessarily have a say in beginning the journey, but now you have to persevere unto some end. They are often used in spiritual mindfulness practices. They introduce order to chaos. Because of the unilateral direction of movement, the unicursal maze is also easier to memorize, so you can remember the design of it after you leave.

Multicursal mazes are the fun ones. There are multiple points of entry and exit, and there are several decisions that you make when you are confronted with junctions in the maze. That is, depending on the path you choose, you may result in a very different place than whether if you chose some other path. The multicursal maze is also perfect to introduce elements of chaos into the design: a bone-crunching minotaur in the center (to avoid) or the tomb of certain gilded Pharaohs (to desire) which may or may not be protected by sacred crocodiles (to avoid). Not all paths are retraceable, and not all paths guarantee an exit. There's definitely a probabilistic element of survival since the end-goal is not guaranteed. In the extra fun versions, you can possibly run into past versions of yourself.

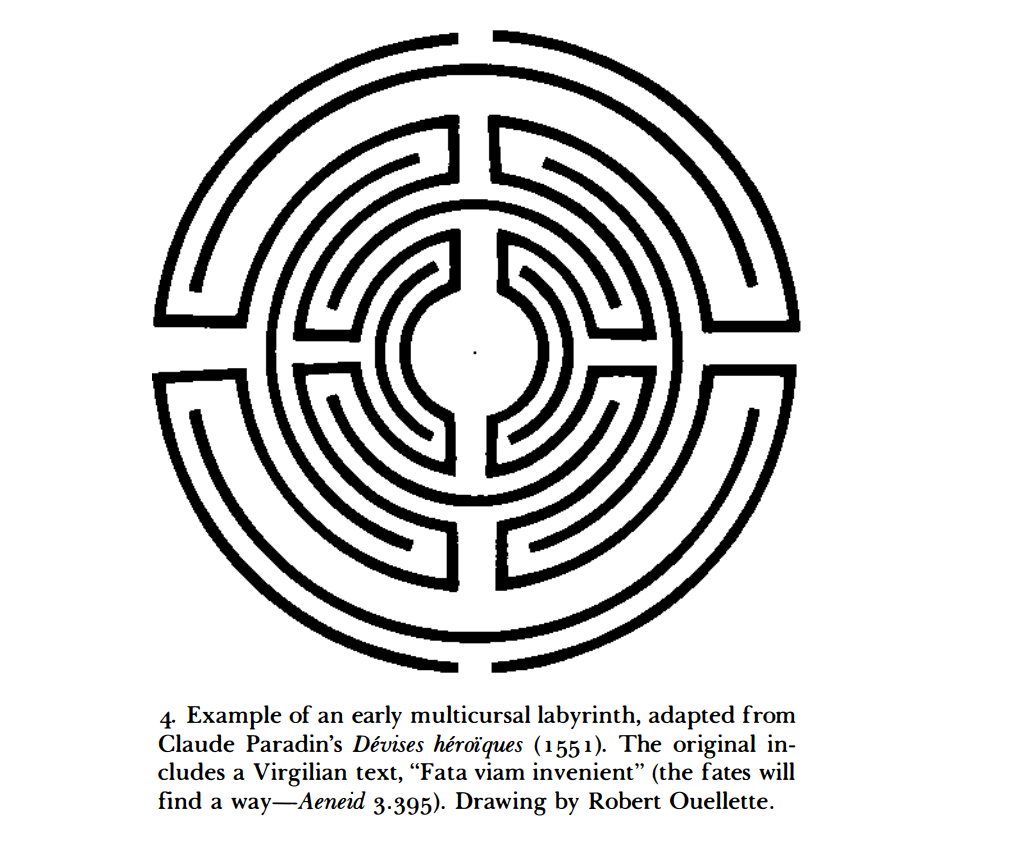

Simplified design of a multicursal maze. Image from Citation 1.

Multicursal mazes are the stuff of heroism and individual skill because they depend on the individual's choices in the environment. Historically, multicursal mazes are created for Rite of Passage rituals and for protecting sacred objects from intruders. This is the kind of maze designed for "creative problem solvers", Pac-man, Indiana Jones, Lara Croft, and oddly enough, people pursuing courtship or extramarital affairs. Usually, this is not the kind of labyrinth for a spiritual mindfulness experience (although your individual experience may vary). These are the mazes with which to introduce chaos.

Labyrinthine designs already exists in multiple forms in nature. Bees create highly-structured hexagonal hives. You could call it a multicursal maze if you had to route a specific path to a specific cell. But hives are also 3D structures where entry and exit is open on all sides. Each cell will usually house a worker bee, unless you've reached the cell of the queen bee (whose cell is highly fortified). There is a concentricity of defense around this design, in that the queen bee and her offspring are kept as protected from external intruders as possible.

Similarly the shell of the chambered nautilus is a growing spiral that the creature develops over its lifetime around the shell. This design is meant to be protective, hiding the creature, making it difficult for external intruders to access its soft bits. The creation and maintenance of this design is calorie-intensive and time-intensive (therefore serving as an indicator of the creature's age). But it is so adaptively successful that the nautilus has not changed this design for nearly 500 million years.

In human history and mythology, Daedalus of Athens built the famous maze which housed the Minotaur inside it, and the only way he himself could escape the maze of his own design was by using a string attached to the opening portal. Despite his engineering prowess, Daedalus and his son were imprisoned once the maze had been solved. This is the same Daedalus whose son, Icarus, flew too close to the sun with wax wings to escape said imprisonment. Many unrelated shenanigans later, he continues with his maze building talents to decorate gates of kings.

Ovid is known for explicitly mentioning that the Greek inspiration for mazes derived from the design of the tombs of the Pharaohs in Egypt. Many of the labyrinths/catacombs and paths to enter and exit the pyramids were carefully planned and extremely difficult to get to. It's important to note that burial rites of the ancient Egyptians included burying an entire staff (of slaves) and many treasures along with the Pharaoh so that he would continue to enjoy a limited-but-similar tier of operational support and wealth-access in the afterlife. Therefore, only the maze-creator, a handful of his team, the rare-but-brilliant grave-robber and (millennia later), archeologists/ Egyptologists would be able to appreciate the complexity and design of a 3D multicursal maze. Essentially, these are examples of mazes that were designed to never be solved.

Ultimately, maze-solving is the parallel task of maze-creation. As human creators and participants, we have to imagine not merely what a labyrinth looks like overhead, but that the experience within the maze can also influence the participant. To create a maze is to ask the question: am I introducing order to chaos or am I introducing chaos only? And if the latter, does the chaos protect something? I also why, out of all the challenges that we create for ourselves, a maze is such a common and heavily-used one. We trust navigation, routing, maps, waiting for systems that have omni-vision to tell us where to go next, and I wonder if that's also not a metaphor for life. That is, are we really directing our own paths or are we constantly calibrating by what external factors tell us we should be doing or making of ourselves?

Spiritual teachers who use labyrinths teach about how, when mazes are traversed by more than one person at a time, they teach us to release and re-meet people at different points in our journey (literally and metaphorically).

To create a maze requires you to consider if you want the entire structure visible to the participant, or do they discover the path as they move from point-to-point in the graph. Maze-solving is tested in lab rodents for hippocampus activity, which is important for learning and memory, and memory is definitely associated with the ability to keep secrets. Sometimes, like Djikstra’s graph-solving algorithm, we might never escape a loop. We might never be able to optimize for the shortest possible path to a point in our lives unless all possible paths are made known, and that multicursal flexibility might never happen. I also wonder if mazes are created to keep the visible a secret, to create the sense of sacredness that we are all losing from rapid immediacy, to trust a process that is unfolding without knowing what the architect intended for us to do.

Citation 1: Doob, Penelope Reed. “The Labyrinth as Significant Form: Two Paradigms.” The Idea of the Labyrinth from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages, Cornell University Press, 1990, pp. 39–63. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctvn1t9v6.8. Accessed 12 Apr. 2023.